One Problem, Four Languages, Two Paradigms

Solving a leetcode problem in four programming languages using two acceleration paradigms!

NOTE: This post is a transcript of the youtube video linked here.

These views do not in any way represent those of NVIDIA or any other organization or institution that I am professionally associated with. These views are entirely my own.In addition to that, we’ll be using various combinations of two programming paradigms common in distributed computing: using a GPU to perform some calculations and MPI to distribute our calculation among multiple processes, potentially on multiple machines.

We’ll be looking at this leetcode problem, which is to determine if a 9 x 9 Sudoku board is valid, but not necessarily solvable. Each row, column, and subbox of the grid must have the digits 1-9.

Let’s jump right in to our BQN solution.

Content

- BQN

- Approach

- Python

- Python And MPI

- C++

- C++ And MPI

- C++ And CUDA

- C++ And CUDA And MPI

- Fortran

- Fortran And MPI

- Conclusion

- YouTube Video Description

BQN

This is what our sudoku boards will look like:

# two 8s in the first block

bad ← ⟨8, 3, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0

6, 0, 0, 1, 9, 5, 0, 0, 0

0, 9, 8, 0, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0

8, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 3

4, 0, 0, 8, 0, 3, 0, 0, 1

7, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 6

0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 8, 0

0, 0, 0, 4, 1, 9, 0, 0, 5

0, 0, 0, 0, 8, 0, 0, 7, 9⟩

# valid sudoku

good ← ⟨5, 3, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0

6, 0, 0, 1, 9, 5, 0, 0, 0

0, 9, 8, 0, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0

8, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 3

4, 0, 0, 8, 0, 3, 0, 0, 1

7, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 6

0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 8, 0

0, 0, 0, 4, 1, 9, 0, 0, 5

0, 0, 0, 0, 8, 0, 0, 7, 9⟩

And here is our full solution. This solution will be the basis for all of our later solutions.

F ← {𝕊𝕩:

Fl ← 0⊸≠⊸/ # Filter 0s out

Dup ← (∨´∾´)¬∘∊¨ # Are there any duplicates?

rs ← Dup Fl¨(9/↕9)⊔𝕩 # Check rows

cs ← Dup Fl¨(81⥊↕9)⊔𝕩 # Check columns

bi ← 27⥊3/↕3

bs ← Dup Fl¨(bi∾(3+bi)∾(6+bi))⊔𝕩 # Check blocks

(bs ∨ rs ∨ cs)⊑"true"‿"false"

}

This first line is a function to filter out any 0s:

Fl ← 0⊸≠⊸/

Fl ⟨5, 3, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0⟩

⟨ 5 3 7 ⟩

Here we have another utility function to return an integer indicating whether any duplicates were found in any sublists:

Dup ← (∨´∾´)¬∘∊¨

Dup ⟨⟨5, 3, 7⟩, ⟨1, 2, 3⟩⟩

0

Dup ⟨⟨5, 3, 7⟩, ⟨1, 2, 2⟩⟩

1

Next we check for duplicates in all the filtered rows and columns:

rs ← Dup Fl¨(9/↕9)⊔𝕩

cs ← Dup Fl¨(81⥊↕9)⊔𝕩

These ranges are used to create indices for grouping the values in X. I’ll show a trimmed down version of their output here to give you an idea:

3‿3⥊(3/↕3) # For the rows

┌─

╵ 0 0 0

1 1 1

2 2 2

┘

3‿3⥊(9⥊↕3) # For the columns

┌─

╵ 0 1 2

0 1 2

0 1 2

┘

Next I do something similar to get the indices for the boxes.

bi ← 27⥊3/↕3

3‿9⥊bi

┌─

╵ 0 0 0 1 1 1 2 2 2

0 0 0 1 1 1 2 2 2

0 0 0 1 1 1 2 2 2

┘

This creats indices for the first three boxes, and you can probably imagine how to extend this to get the indices for all the boxes. I just add three to the previous indices, and then add six, and then append them all together. Here’s the second layer:

3‿9⥊bi+3

┌─

╵ 3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5

3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5

3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5

┘

And the final layer:

3‿9⥊bi+6

┌─

╵ 6 6 6 7 7 7 8 8 8

6 6 6 7 7 7 8 8 8

6 6 6 7 7 7 8 8 8

┘

And all three layers of indices stacked on top of each other:

9‿9⥊(bi∾(3+bi)∾(6+bi))

┌─

╵ 0 0 0 1 1 1 2 2 2

0 0 0 1 1 1 2 2 2

0 0 0 1 1 1 2 2 2

3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5

3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5

3 3 3 4 4 4 5 5 5

6 6 6 7 7 7 8 8 8

6 6 6 7 7 7 8 8 8

6 6 6 7 7 7 8 8 8

┘

Using these indices, I group all the elements of the input, and then check all of them for duplicates:

bs ← Dup Fl¨(bi∾(3+bi)∾(6+bi))⊔𝕩 # Check blocks

And in the end I check if there were duplicates in the blocks, in the rows, or in the columns, and use that to index into our strings that indicate whether our sudoku board is valid or not.

(bs ∨ rs ∨ cs)⊑"true"‿"false"

Approach

Before we move on to the Python solution, I’d like to talk about our approach to this solution in the rest of the languages, because they will all be pretty similar.

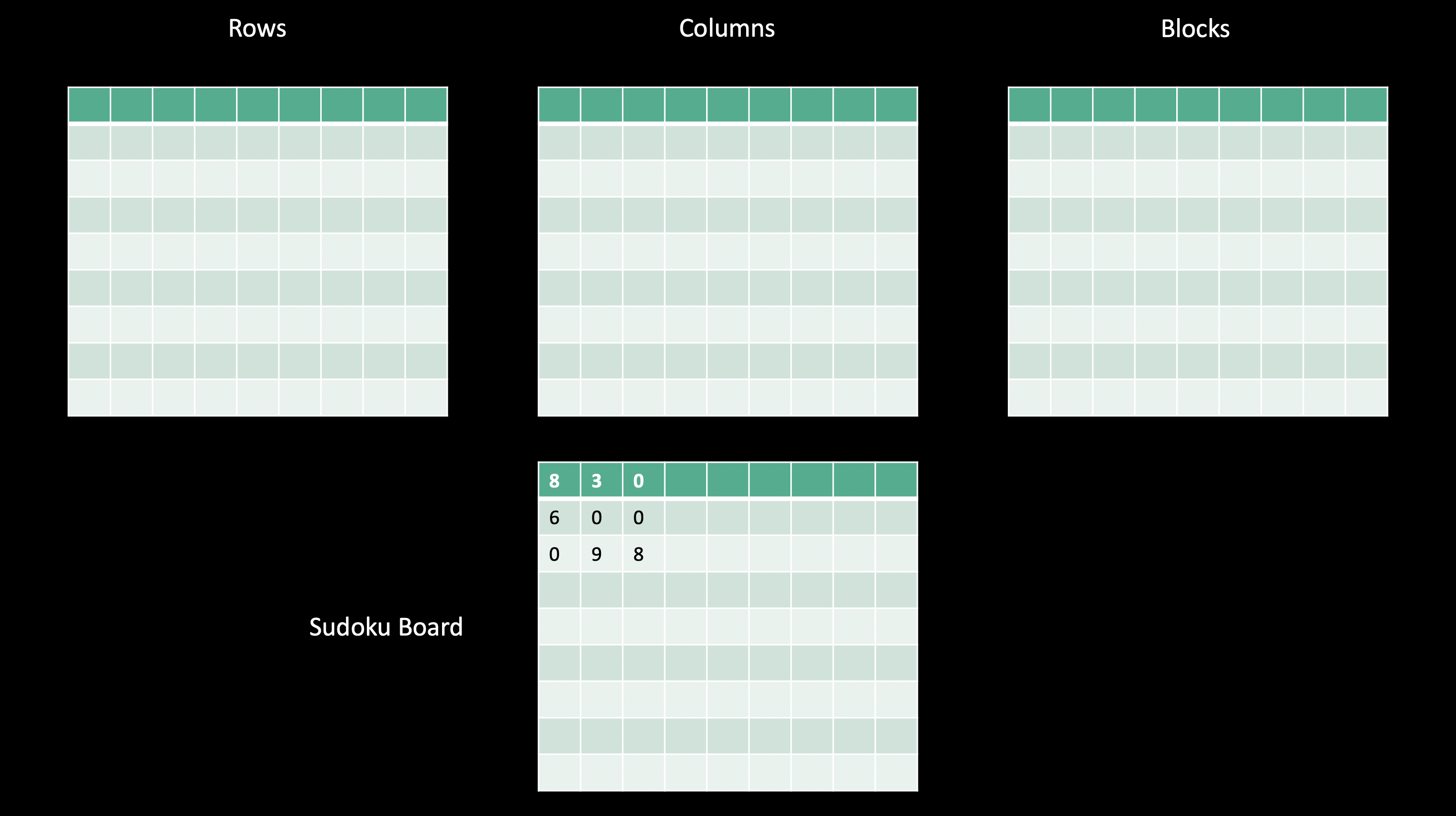

Just like in the BQN solution, we have three collections which represent the validity of the rows, another for the columns, and a third for the blocks.

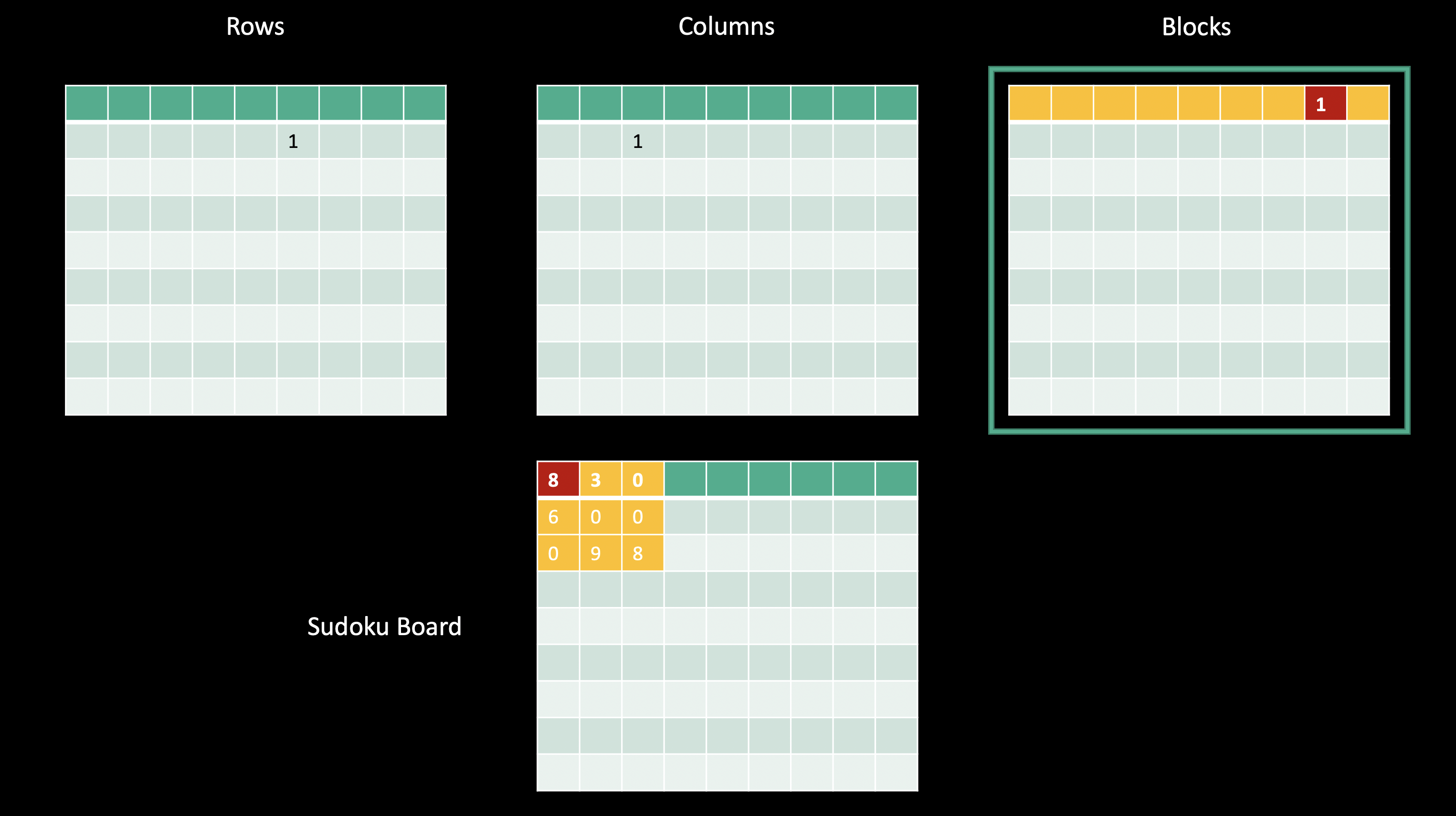

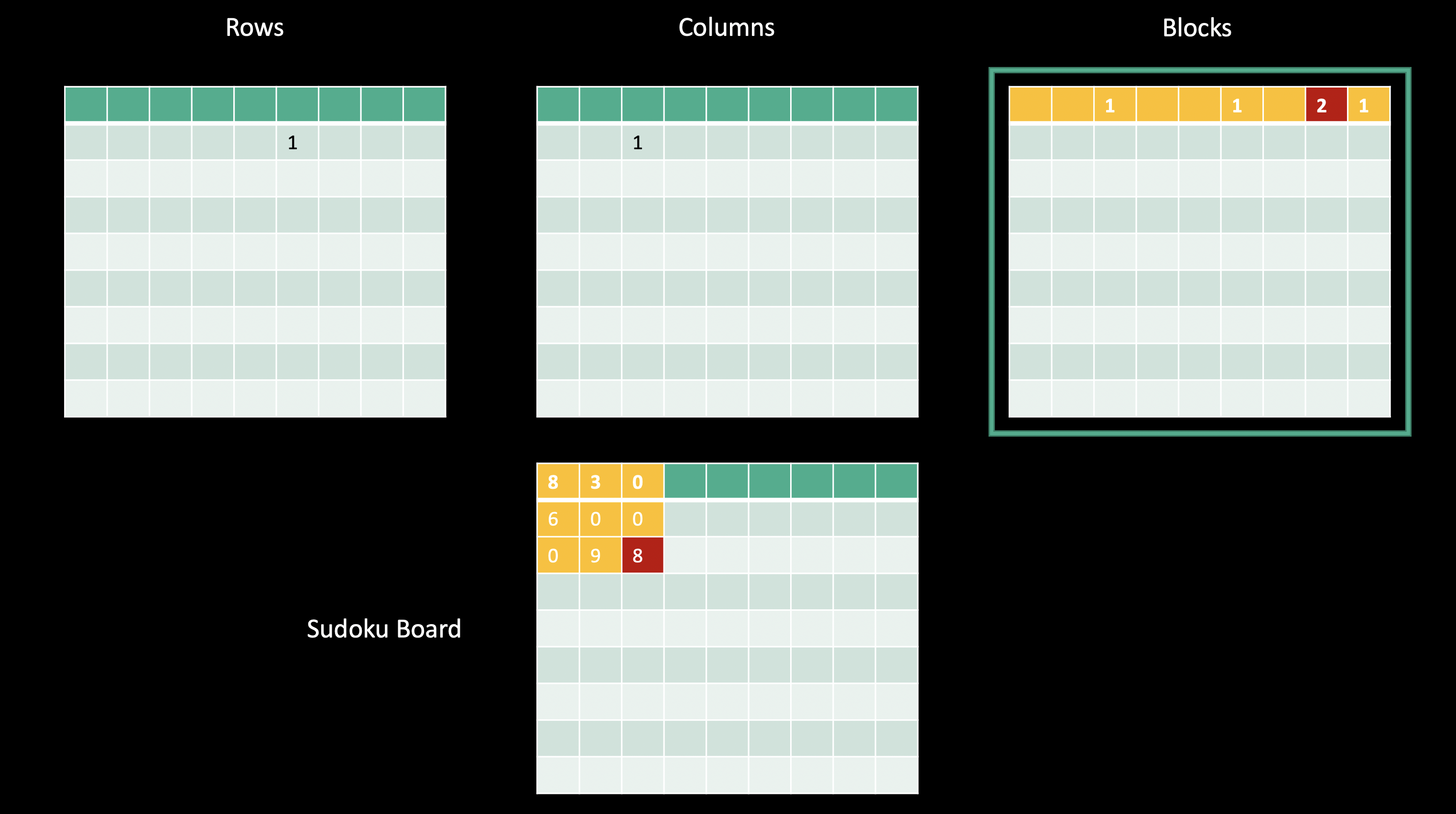

Here I have a subset of a sudoku board on the bottom.

In our procedural languages, we’ll create an array thrice the size of the grid to hold these values.

Note that this is not as space (or time) efficient as many of the solutions that you can find on the discussion page for the leetcode problem, but it is much easier to parallelize and that’s really the point of this video.

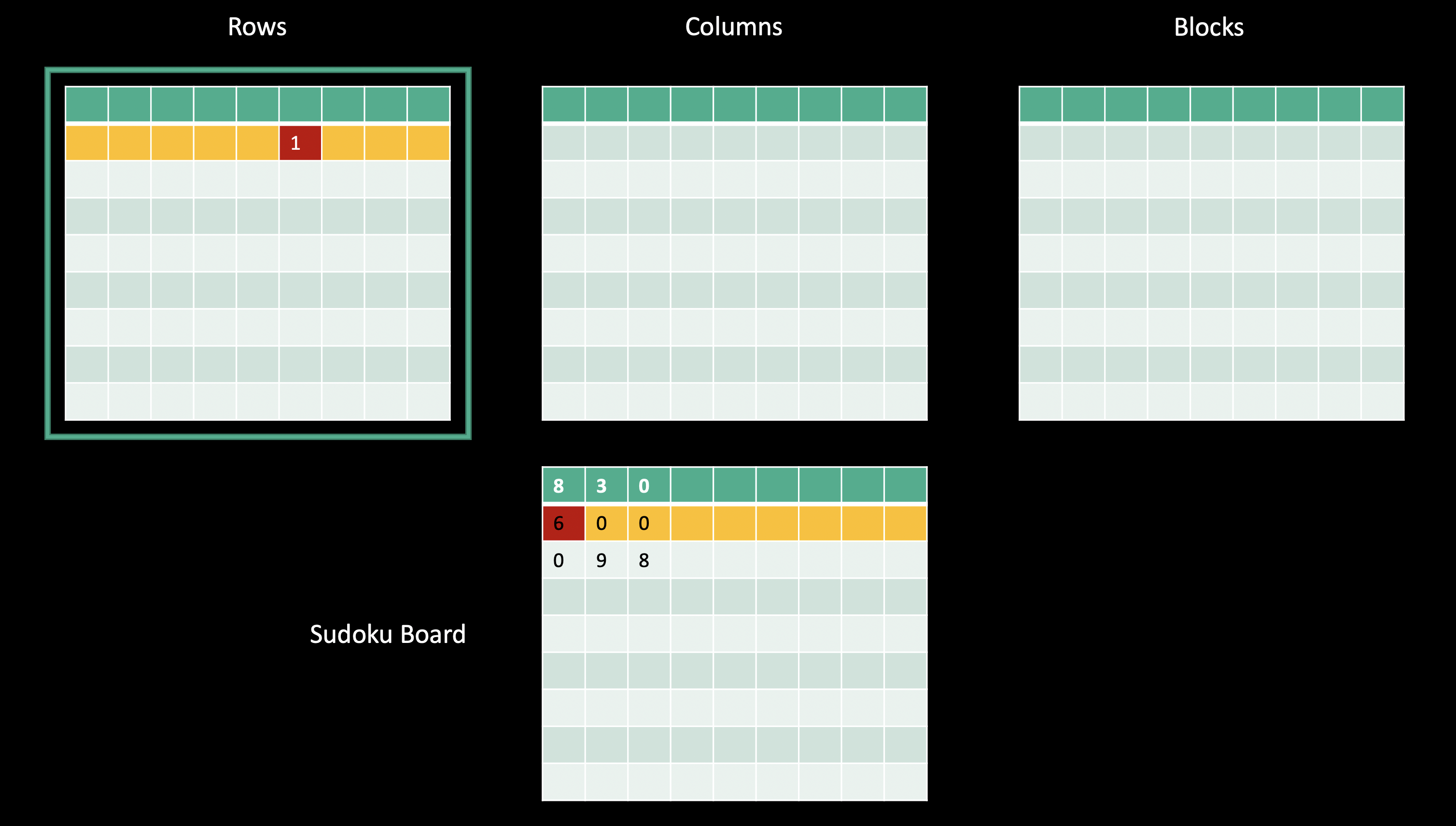

Let’s now walk through a few steps of our algorithm starting at the second row and first column of our sudoku board, which relates to the second row of our “row matrix.”

Because we’re looking at our row matrix, we’ll take the row index in our sudoku board as the row for our row matrix, and we’ll take the value in the cell, in this case 6, as the column in our row matrix. We’ll increment the value at this location in our row matrix, or in the first layer of our 3-d sum matrix that we’ll use to get our final answer.

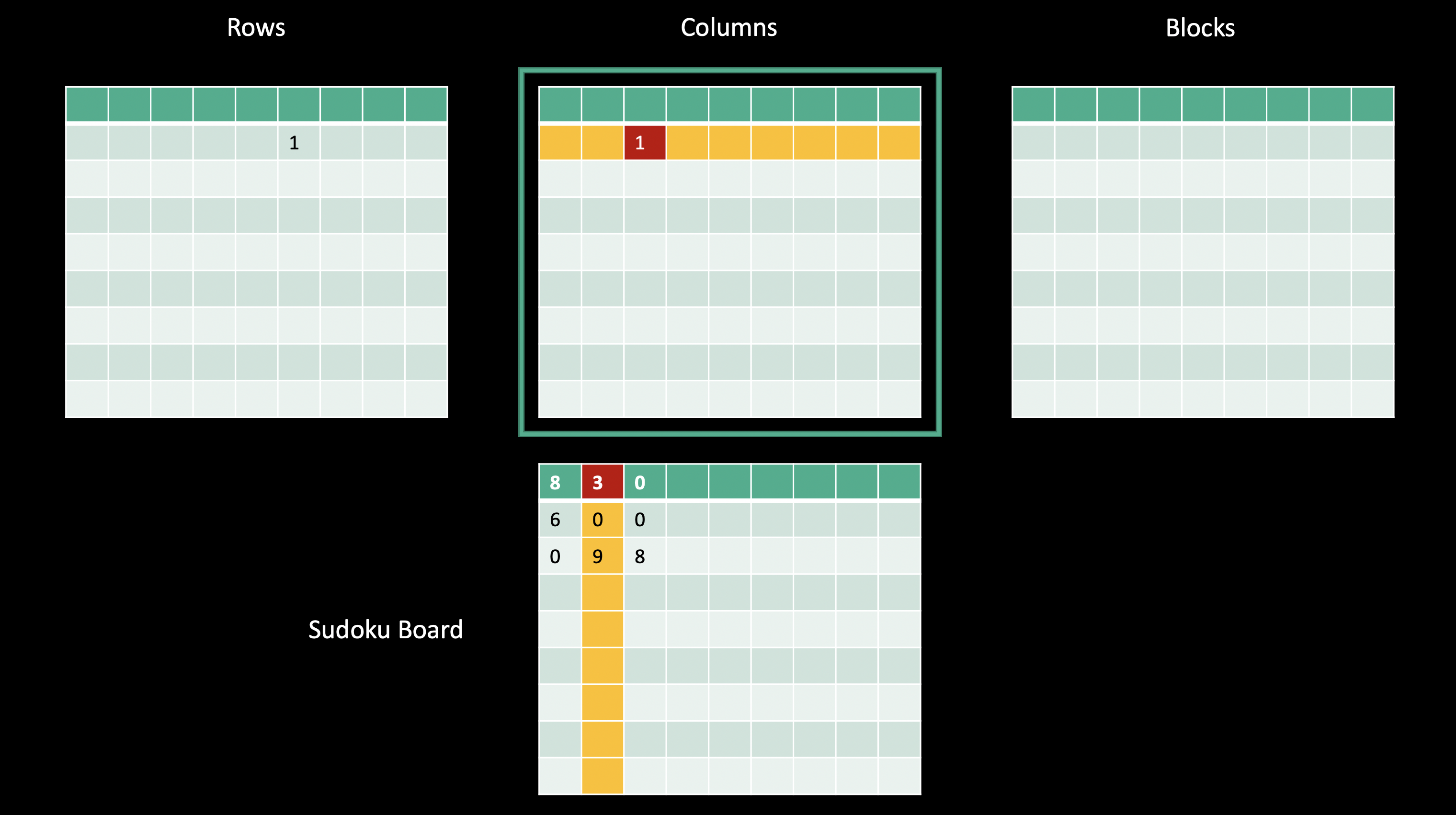

Let’s move on to check the first row and second column of our sudoku board for our column matrix. Because we’re looking at our column matrix, or the second layer of our final sum array, we’ll use the column index as the row index in our column matrix, and the value in that cell for the column index in our column matrix.

We’ll increment the value at this location in our column matrix, or in the second layer of our 3-d sum matrix that we’ll use to get our final answer.

Finally, let’s look at the first block in our sudoku board, which corresponds to the first row in our block matrix, and let’s look at the first cell in that block. The value in the first cell in the first block is 8, so we’ll increment the first row and eighth column in our block matrix.

If we then perform these three operations for every cell in the sudoku board, we’ll have a final matrix that indicates all the row-column-block-value combinations that we have, and if any cell in that final matrix has a value greater than one, then our board is invalid.

If we were then to check the final cell in the first block of our board, we would find that the eighth element of the first row of our block matrix would be incremented again, which would mean we have an invalid board!

If any value in our final array is greater than one, then we know we have at least one duplicate in at least one row, column, or block.

What’s neat about this solution is that no single operation depends on any other operation as long as we perform our operations atomically. This way, our work can be performed on multiple machines or different devices, and as long as we synchronize at the end, our solution will be the same.

Now that we’ve talked strategy, let’s see what this looks like in our Python solution.

Python

Here’s our simple Python solution:

shape = 9

blksz = 3

def solve(board):

ar = [[[0 for j in range(3)] for i in range(shape)] for k in range(shape)]

for r in range(shape):

for c in range(shape):

v = board[r][c]

if 0 == v:

continue

ar[r][v - 1][0] += 1

ar[c][v - 1][1] += 1

bi = (r // blksz) * blksz + (c // blksz)

ar[bi][v - 1][2] += 1

return max(max(i) for j in ar for i in j) < 2

You can see here that we increment the value in the first layer of our full 3D matrix according to the row and the value in the cell currently being examined:

ar[r][v - 1][0] += 1

We do the same for our column matrix:

ar[c][v - 1][1] += 1

And finally for our block matrix, it just takes a little bit of math to figure out what our block index is.

bx = r // blksz

by = c // blksz

bi = bx * blksz + by

ar[bi][v - 1][2] += 1

I use this main function to run the python solution:

if __name__ == "__main__":

for b in sudoku_9x9.boards():

print(solve(b))

We run our example with two valid boards and two invalid boards and get the answers we expect:

$ python ./src/python/lc-valid-sudoku.py

True

True

False

False

Python And MPI

Now we’ll look at another python example, but this time one that uses MPI to distribute the calculations.

MPI provides a lot of infrastructure for distributed computing: using the mpirun command spawns N processes, each of which knows how many processes were spawned, what its unique process ID is, and some other relevant information.

These processes may be spawned on multiple machines even, and MPI gives us the tools to communicate between these processes.

We’ll take advantage of this infrastructure to perform our calculations on multiple processes.

import numpy as np

from mpi4py import MPI

shape = 9

blksz = 3

comm = MPI.COMM_WORLD

def solve(board, comm):

ar = np.zeros((9, 9, 3), dtype=np.int64)

chunk = (81 + comm.size - 1) // comm.size

subscripts = (*itertools.product(range(9), range(9)),)

for i in range(comm.rank * chunk, (comm.rank * chunk) + chunk):

if i >= 81:

break

r, c = subscripts[i]

v = board[r][c]

if 0 == v:

continue

ar[r][v - 1][0] += 1

ar[c][v - 1][1] += 1

bi = (r // blksz) * blksz + (c // blksz)

ar[bi][v - 1][2] += 1

gar = np.zeros((9 * 9 * 3,), dtype=np.int64)

comm.Reduce([ar.flatten(), MPI.INT], [gar, MPI.INT], op=MPI.SUM, root=0)

comm.Barrier()

return max(gar.flatten()) < 2 if 0 == comm.rank else False

This is what the setup looks like to get an MPI program running.

if __name__ == "__main__":

if 0 == comm.rank:

print("Running with size {0}".format(comm.size))

for b in sudoku_9x9.boards():

comm.Barrier()

if 0 == comm.rank:

ret = solve(b, comm)

print(ret)

else:

solve(b, comm)

Here we chunk our work up based on how many processes we have:

chunk = ((9 * 9) + comm.size - 1) // comm.size

Say we’re given 5 processes and we have 81 cells to check (because that’s the size of our sudoku board). The calculation would look something like this:

chunk is then the smallest amount of work for each process such that all the work that needs to be done is performed.

This is a common calculation that needs to be done in parallel computing.

Note that our final process may exit early if the work is not evenly divisible by the chunk size.

>>> work = 81

>>> size = 5

>>> chunk = (work + size - 1) // size

>>> chunk

17

>>> chunk * size

85

We then generate all the possible combinations of rows and columns, and iterate over only the elements that fall within the chunk of work that belongs to our current MPI process.

subscripts = (*itertools.product(range(9), range(9)),)

for i in range(comm.rank * chunk, (comm.rank * chunk) + chunk):

if i >= work:

break

r, c = subscripts[i]

The rest of this code is exactly the same as our serial implementation:

v = board[r][c]

if 0 == v:

continue

ar[r][v - 1][0] += 1

ar[c][v - 1][1] += 1

bi = (r // blksz) * blksz + (c // blksz)

ar[bi][v - 1][2] += 1

This next bit is more interesting.

We create a global array with the size we need to hold our final sum matrix, and we use the MPI function Reduce.

This function will perform the operation op, in this case MPI.SUM, to join the arrays ar and gar together on rank 0 specified by the root argument.

This means that our final summed matrix for all components of the solution is on the MPI process with rank 0.

We can then check if we have any cells with values greater than one, and return that value if we’re on rank 0.

Otherwise, we can just return false since no other rank has the final array.

gar = np.zeros((9 * 9 * 3,), dtype=np.int64)

comm.Reduce([ar.flatten(), MPI.INT], [gar, MPI.INT], op=MPI.SUM, root=0)

comm.Barrier()

return max(gar.flatten()) < 2 if 0 == comm.rank else False

Here I run the example on 5 processes, and we see we get the same solution as with our serial example.

$ mpirun -n 5 python ./src/python/lc-valid-sudoku-mpi.py

Running with size 5

True

True

False

False

Now let’s move on to all our C++ solutions.

C++

All of our C++ solutions will use a board like this:

const auto board = std::array<int, 81>{

5, 3, 0, 0, 7, 0, 0, 0, 0,

6, 0, 0, 1, 9, 5, 0, 0, 0,

0, 9, 8, 0, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0,

8, 0, 0, 0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 3,

4, 0, 0, 8, 0, 3, 0, 0, 1,

7, 0, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 0, 6,

0, 6, 0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 8, 0,

0, 0, 0, 4, 1, 9, 0, 0, 5,

0, 0, 0, 0, 8, 0, 0, 7, 9

};

Here’s our serial C++ solution.

auto isgood(const std::array<int, 81> &board) -> bool {

auto ar = std::vector<int>(9 * 9 * 3, 0);

for (int r = 0; r < 9; r++)

for (int c = 0; c < 9; c++) {

const auto v = board[idx2(r, c)];

if (0 == v)

continue;

ar[idx3(r, v - 1, 0)] += 1;

ar[idx3(c, v - 1, 1)] += 1;

const auto bi = (r / blksz) * blksz + (c / blksz);

ar[idx3(bi, v - 1, 2)] += 1;

}

const auto m =

std::accumulate(ar.begin(), ar.end(), -1, max);

return m < 2;

}

You can see pretty much everything about our solution is the same so far.

You may notice the idx2 and idx3 functions - these just calculate the linear index from subscripts so we can almost use 2d and 3d subscripts while keeping our arrays totally linear.

Here’s our idx2 function for example. I’ll be using these functions for the rest of my solutoins since they make the code much more readable.

int idx2(int r, int c) {

return (r * 9) + c;

};

Here at the end I find the max value again and check to make sure it’s less than two:

const auto m =

std::accumulate(ar.begin(), ar.end(), -1, max);

return m < 2;

Running our executable gives us the same answers as our previous implementations:

$ ./src/cpp/lc-valid-sudoku

true

true

false

false

C++ And MPI

Here we have our MPI distributed C++ solution, let’s walk through it in a few steps.

auto isgood(const std::array<int, 81> &board, int rank, int size) -> bool {

const auto chunk = (81 + size - 1) / size;

auto ar = std::vector<int>(81 * 3, 0);

auto indices = std::vector<std::pair<int, int>>(81 * size, std::make_pair(-1, -1));

for (int r = 0; r < 9; r++)

for (int c = 0; c < 9; c++)

indices[idx2(r, c)] = std::make_pair(r, c);

for (std::size_t i = chunk * rank; i < chunk + (chunk * rank); i++) {

const auto &[r, c] = indices[i];

const auto v = board[idx2(r, c)];

if (r < 0 or 0 == v) continue;

ar[idx3(r, v - 1, 0)] += 1;

ar[idx3(c, v - 1, 1)] += 1;

const auto bi = (r / blksz) * blksz + (c / blksz);

ar[idx3(bi, v - 1, 2)] += 1;

}

std::vector<int> gar(9 * 9 * 3, 0);

MPI_Reduce(ar.data(), gar.data(), gar.size(), MPI_INT, MPI_SUM, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

return 0 == rank ? std::accumulate(gar.begin(), gar.end(), -1, std::max) < 2

: false;

}

All the setup is the same between the last several solutions.

Astute viewers may recognize this as a cartesian product, but I couldn’t find a nice way to do this with the STL algorithms. If any viewers know of a nicer way to generate the cartesian product of two containers, please let me know.

for (int r = 0; r < 9; r++)

for (int c = 0; c < 9; c++)

indices[idx2(r, c)] = std::make_pair(r, c);

The core loop is much the same as our other solutions, aside from unpacking the row and column as a tuple.

for (std::size_t i = chunk * rank; i < chunk + (chunk * rank); i++) {

const auto &[r, c] = indices[i];

const auto v = board[idx2(r, c)];

if (r < 0 or 0 == v)

continue;

ar[idx3(r, v - 1, 0)] += 1;

ar[idx3(c, v - 1, 1)] += 1;

const auto bi = (r / 3) * 3 + (c / 3);

ar[idx3(bi, v - 1, 2)] += 1;

}

This section is exactly equivilant to the Python version below. This should give you an idea of what it’s like to use the raw C and Fortran interfaces to MPI.

std::vector<int> gar(9 * 9 * 3, 0);

MPI_Reduce(ar.data(), gar.data(), gar.size(), MPI_INT, MPI_SUM, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

return 0 == rank ? std::accumulate(gar.begin(), gar.end(), -1, sb::max) < 2

: false;

Python version:

gar = np.zeros((9 * 9 * 3,), dtype=np.int64)

comm.Reduce([ar.flatten(), MPI.INT], [gar, MPI.INT], op=MPI.SUM, root=0)

comm.Barrier()

return max(gar.flatten()) < 2 if 0 == comm.rank else False

In my main function I iterate over the same boards and use some extra logic so we only see the results that rank 0 gave back:

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

int size, rank;

MPI_Init(&argc, &argv);

MPI_Comm comm = MPI_COMM_WORLD;

MPI_Comm_size(comm, &size);

MPI_Comm_rank(comm, &rank);

for (const auto &board : all_boards) {

bool ret;

if (0 == rank) {

ret = isgood(board, rank, size);

std::cout << bool2str(ret) << "\n";

} else isgood(board, rank, size);

MPI_Barrier(comm);

}

MPI_Finalize();

return 0;

}

Running this works just as all our previous solutions did:

$ mpirun -n 5 ./src/cpp/lc-valid-sudoku-mpi

true

true

false

false

We’ll now take a look at our CUDA-enabled solution.

C++ And CUDA

Here’s our single-process CUDA implementation. I for the most part am using raw CUDA, but I use a few helper methods from Thrust as well, such as the type-safe device malloc and free and some pointer-casting methods. For those that are unfamiliar, the funny-looking function calls with the triple braces are how you launch a raw cuda kernel. These allow you to pass arguments to the CUDA runtime to let it know how you’d like your CUDA kernel to be launched.

auto isgood(const Board &board) -> bool {

auto d_ar = device_malloc<int>(81 * 3);

setar<<<1, dim3(9, 9)>>>(

raw_pointer_cast(d_ar),

raw_pointer_cast((thrust::device_vector<int>(board.begin(), board.end())).data()));

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

const auto m = thrust::reduce(d_ar, d_ar+(81*3), -1, thrust::maximum<int>());

device_free(d_ar);

return m < 2;

}

I have the following using statements to make the code a little more readable hopefully.

using thrust::device_malloc;

using thrust::device_free;

using thrust::device_vector;

using thrust::host_vector;

using thrust::raw_pointer_cast;

Along with the previous code that should look pretty familiar at this point, I define two other CUDA kernels.

The first is this short setrc kernel, which sets rows and columns based on the kernel launch parameters I pass.

This is a shortcut for a cartesian product of the rows and columns that runs on the GPU.

__global__ void setrc(int *rows, int *cols) {

const int r = threadIdx.x, c = threadIdx.y;

rows[idx2(r, c)] = r;

cols[idx2(r, c)] = c;

}

The other kernel is this setar function, which is the same core kernel that’s been at the heart of all of our solutions so far.

__global__ void setar(int *ar, const int *board) {

const auto row = threadIdx.x, col = threadIdx.y;

const int value = board[idx2(row, col)];

if (0 == value) return;

atomicAdd(&ar[idx3(row, value, 0)], 1);

atomicAdd(&ar[idx3(col, value, 1)], 1);

const int bi = (row / blksz) * blksz + (col / blksz);

atomicAdd(&ar[idx3(bi, value, 2)], 1);

}

Outside of those two kernels, the solution should look pretty familiar at this point. We allocate our final array and pass it to our cuda kernel, along with the sudoku board after copying it to the GPU.

auto d_ar = device_malloc<int>(81 * 3);

setar<<<1, dim3(9, 9)>>>(

raw_pointer_cast(d_ar),

raw_pointer_cast(

(device_vector<int>(board.begin(), board.end())).data()

)

);

We then syncronize with our GPU to make sure the kernel finishes before reducing to find the maximum value with thrust::reduce, freeing our device memory, and returning whether all values fell below two.

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

const auto m = thrust::reduce(d_ar, d_ar+(81*3), -1, thrust::maximum<int>());

device_free(d_ar);

return m < 2;

Let’s move on to our most complex example, the C++ CUDA-enabled, MPI-distributed implementation.

C++ And CUDA And MPI

Now that we’re using two extra paradigms, CUDA GPU device offloading and MPI distributed computing, our code is looking more noisy. It’s still pretty much the same solution as our non-distributed CUDA solution though.

auto isgood(const Board &board, int rank, int size) -> bool {

const auto chunk = (81 + size - 1) / size;

const auto rows = device_malloc<int>(chunk * size),

cols = device_malloc<int>(chunk * size);

thrust::fill(rows, rows + (chunk * size), -1);

setrc<<<1, dim3(9, 9)>>>(raw_pointer_cast(rows), raw_pointer_cast(cols));

auto d_ar = device_malloc<int>(81 * 3);

thrust::fill(d_ar, d_ar + (81 * 3), 0);

setar<<<1, chunk>>>(

raw_pointer_cast(d_ar),

raw_pointer_cast((device_vector<int>(board.begin(), board.end())).data()),

raw_pointer_cast(rows), raw_pointer_cast(cols), chunk * rank);

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

auto h_ar = host_vector<int>(d_ar, d_ar + (81 * 3));

auto gar = host_vector<int>(81 * 3, 0);

MPI_Reduce(h_ar.data(), gar.data(), gar.size(), MPI_INT, MPI_SUM, 0,

MPI_COMM_WORLD);

device_free(rows); device_free(cols); device_free(d_ar);

if (rank > 0)

return false;

const auto m = thrust::reduce(thrust::host, gar.begin(), gar.end(), -1,

thrust::maximum<int>());

return m < 2;

}

The setar kernel is a bit different from our non distributed CUDA solution since we’re only operating on a subset of our sudoku board.

We set the values in our final sum matrix for the row, column and block submatrices just like before.

This time however, we’re given this offset parameter.

This is because we’re not just running CUDA kernels, we’re running CUDA kernels on multiple processes and potentially multiple machines, so we’re only performing a subset of the full set of operations.

This offset parameter tells us where we should start relative to the entire set of operations.

We’re also not using the builtin threadIdx.y value since we’re launching our kernel in a 1D grid with precalculated row and column indices instead of a 2D grid.

__global__ void setar(int *ar, const int *board, const int *rows,

const int *cols, const int offset) {

const auto i = offset + threadIdx.x;

const int r = rows[i], c = cols[i];

const int value = board[idx2(r, c)];

if (r < 0 || 0 == value)

return;

atomicAdd(&ar[idx3(r, value, 0)], 1);

atomicAdd(&ar[idx3(c, value, 1)], 1);

const int bi = (r / blksz) * blksz + (c / blksz);

atomicAdd(&ar[idx3(bi, value, 2)], 1);

}

If we return to the start of our top-level function, you’ll see that we calculate the work that should be performed on this MPI process. We also set up our row and column indices using our cartesian product kernel.

const auto chunk = (81 + size - 1) / size;

const auto rows = device_malloc<int>(chunk * size),

cols = device_malloc<int>(chunk * size);

thrust::fill(rows, rows + (chunk * size), -1);

setrc<<<1, dim3(9, 9)>>>(raw_pointer_cast(rows), raw_pointer_cast(cols));

We then set up our final sum matrix on the device:

auto d_ar = device_malloc<int>(81 * 3);

thrust::fill(d_ar, d_ar + (81 * 3), 0);

And then launch our core kernel to perform the operations assigned to the current rank:

setar<<<1, chunk>>>(

raw_pointer_cast(d_ar),

raw_pointer_cast((device_vector<int>(board.begin(), board.end())).data()),

raw_pointer_cast(rows), raw_pointer_cast(cols), chunk * rank);

We syncronize with our GPU device and copy the data to a host vector before reducing the final sum array across all of our ranks using MPI. Note that if we used a GPU-enabled MPI provider we could send the data on the device directly to another system’s GPU without copying the memory to the host, but this has other complications so I kept it simple for this example.

cudaDeviceSynchronize();

auto h_ar = host_vector<int>(d_ar, d_ar + (81 * 3));

auto gar = host_vector<int>(81 * 3, 0);

MPI_Reduce(h_ar.data(), gar.data(), gar.size(), MPI_INT, MPI_SUM, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD);

And then we perform our final reduction on our root rank to see if we have any cells with values greater than 1. We could perform this reduction on the device, but it’s probably not worth it to copy the data back to the device for just one operation.

if (rank > 0)

return false;

const auto m = thrust::reduce(thrust::host, gar.begin(), gar.end(), -1,

thrust::maximum<int>());

return m < 2;

And there we have it, our sudoku validator is running on multiple processes and using GPUs.

$ mpirun -n 7 ./src/thrust/lc-valid-sudoku-mpi-thrust

true

true

false

false

Now let’s move on to Fortran.

Fortran

You’re likely not surprised that this looks a lot like our previous solutions.

subroutine isgood(board, ret)

implicit none

integer, dimension(0:(shape*shape)-1), intent(in) :: board

logical, intent(out) :: ret

integer, dimension(0:(shape * shape * 3)-1) :: ar

integer :: v, row, col, i, bx, by

ar = 0

do row = 0, shape-1

do col = 0, shape-1

v = board(idx2(row, col))

if (v .eq. 0) cycle

ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)) = ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)) + 1

ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)) = ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)) + 1

ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)) = ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)) + 1

end do

end do

v = maxval(ar) - 1

ret = (v .lt. 1)

end subroutine isgood

If I clear away the declarations and initializations, this looks fairly readable. You may notice that I have to repeat myself a few times because there’s not a really nice way to incremenet a value in fortran.

subroutine isgood(board, ret)

do row = 0, shape-1

do col = 0, shape-1

v = board(idx2(row, col))

if (v .eq. 0) cycle

ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)) = ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)) + 1

ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)) = ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)) + 1

ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)) = ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)) + 1

end do

end do

v = maxval(ar) - 1

ret = (v .lt. 1)

end subroutine isgood

Now we move on to the MPI-distributed Fortran implementation. This solution is pretty long so I’ll break the function into a few slides like a sliding window.

Fortran And MPI

Here is the full solution.

subroutine isgood(board, ret)

use mpi

implicit none

integer, dimension(shape*shape), intent(in) :: board

logical, intent(out) :: ret

integer, dimension(shape * shape * 3) :: ar, gar

integer, dimension(shape * shape) :: rows, cols

integer :: v, row, col, i, chunk, rank, size, ierr

ar = 0

gar = 0

call MPI_Comm_rank(MPI_COMM_WORLD, rank, ierr)

call MPI_Comm_size(MPI_COMM_WORLD, size, ierr)

do row = 0, shape-1

do col = 0, shape-1

rows(1+idx2(row, col)) = row

cols(1+idx2(row, col)) = col

end do

end do

chunk = ((shape*shape) + size - 1) / size

do i = 1+(rank*chunk), (rank*chunk)+chunk

if (i .gt. (shape*shape)) exit

row = rows(i)

col = cols(i)

v = board(1+idx2(row, col))

if (v .eq. 0) cycle

ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)+1) = ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)+1) + 1

ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)+1) = ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)+1) + 1

ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)+1) = ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)+1) + 1

end do

call MPI_Reduce(ar, gar, 3*shape*shape, MPI_INT, MPI_SUM, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, ierr)

call MPI_Barrier(MPI_COMM_WORLD, ierr)

if (0 .eq. rank) then

v = maxval(gar) - 1

ret = (v .lt. 1)

else

ret = .false.

end if

end subroutine isgood

Let’s trim away the declarations and initializations again:

subroutine isgood(board, ret)

do row = 0, 8

do col = 0, 8

rows(1+idx2(row, col)) = row

cols(1+idx2(row, col)) = col

end do

end do

chunk = (81 + size - 1) / size

do i = 1+(rank*chunk), (rank*chunk)+chunk

if (i .gt. 81) exit

row = rows(i)

col = cols(i)

v = board(1+idx2(row, col))

if (v .eq. 0) return

ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)+1) = ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)+1) + 1

ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)+1) = ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)+1) + 1

ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)+1) = ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)+1) + 1

end do

call MPI_Reduce(ar, gar, 3*81, MPI_INT, MPI_SUM, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, ierr)

call MPI_Barrier(MPI_COMM_WORLD, ierr)

if (0 .eq. rank) then

v = maxval(gar) - 1

ret = (v .lt. 1)

else

ret = .false.

end if

end subroutine isgood

You’ll notice that I create row and column arrays again because this makes distributing the processes much simpler.

do row = 0, 8

do col = 0, 8

rows(1+idx2(row, col)) = row

cols(1+idx2(row, col)) = col

end do

end do

The core loop is the same as the other distributed solutions. I work only on the rows and columns assigned to the current rank.

do i = 1+(rank*chunk), (rank*chunk)+chunk

if (i .gt. 81) exit

row = rows(i)

col = cols(i)

v = board(1+idx2(row, col))

if (v .eq. 0) return

ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)+1) = ar(idx3(row, v-1, 0)+1) + 1

ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)+1) = ar(idx3(col, v-1, 1)+1) + 1

ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)+1) = ar(idx3(bi(row, col), v-1, 2)+1) + 1

end do

We reduce the solution across all of our ranks to get the full array on rank 0. We then perform our max reduce to get our answer and we return!

call MPI_Reduce(ar, gar, 3*81, MPI_INT, MPI_SUM, 0, MPI_COMM_WORLD, ierr)

call MPI_Barrier(MPI_COMM_WORLD, ierr)

if (0 .eq. rank) then

v = maxval(gar)

ret = (v .lt. 2)

else

ret = .false.

end if

Running this gives us the answers we expect.

$ mpirun -n 7 ./src/fortran/lc-valid-sudoku-ftn-mpi

Running with world size of 7

T

T

F

F

Conclusion

I hope you’ve all enjoyed this video and the foray into distributed computing in a few different programming languages.

Contact

You can reach me at any of the links below:

These views do not in any way represent those of NVIDIA or any other organization or institution that I am professionally associated with. These views are entirely my own.YouTube Description

We solve a Leetcode problem in four languages using various combinations of MPI and CUDA!

- 0:00 Problem Introduction

- 0:36 BQN Solution

- 2:07 Solution Strategy

- 4:54 Python Solution

- 5:42 Python & MPI Solution

- 8:01 C++ Solution

- 8:55 C++ & MPI Solution

- 9:58 C++ & CUDA Solution

- 11:24 C++ & MPI & CUDA Solution

- 13:31 Fortran Solution

- 13:55 Fortran & MPI Solution

-

14:38 Conclusion

- Written version: http://www.ashermancinelli.com/leetcode-distributed-computing

- LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/asher-mancinelli-bb4a56144/

- GitHub Repo for Examples: https://github.com/ashermancinelli/algorithm-testbed